“No matter how good or bad you are at singing and dancing”

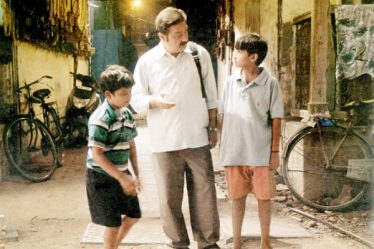

Shanu (9) and Bua (7) live in Mumbai. Since their father died, mum is struggling hard to make enough money. That’s why she asks her brother-in-law to find the kids a job. That’s how they come to enter the film industry, serving chai on a Bollywood film set.

Shanu (9) and Bua (7) live in Mumbai. Since their father died, mum is struggling hard to make enough money. That’s why she asks her brother-in-law to find the kids a job. That’s how they come to enter the film industry, serving chai on a Bollywood film set.

But with the job also comes a new passion: playing ‘chidiya’ (badminton). This is a passion not easily cherished, as besides shuttlecocks, a net and a court, you also need time to play. Shanu and Bua scramble vigorously to make that dream come true.

Filmmaker Mehran Amrohi does not only prove his talent for vibrant cinema with a touch of local charm, but proves himself equally qualified for a perfect Q & A. He chats away, adding funny anecdotes that refer to his childhood days and complementing the crowd on their clever questions. “I believe in destiny. It was my faith to be here: the reputation of the Zlin Festival as one of the oldest and biggest children’s film festivals in Europe is widely spread, and it was always my dream to come here one day. I’ve only made my first film and here I am already!”

The film stays true to most conventions of Indian moviemaking.

The film stays true to most conventions of Indian moviemaking.

Amrohi: There is a bit of singing and dancing in this movie, because there is singing and dancing in everything we do. Indian people celebrate a lot. It’s a vital part of our film culture and our everyday life, no matter how good or bad you are at singing and dancing.

Is badminton also an essential part of that culture?

Amrohi: It wasn’t in my childhood days, but since Saina Nehwal became World Champion, badminton is the second most popular sport in India. In general every Indian sports film will tell about cricket – even in CHIDIYA there is one cricket scene, apparently it’s hard to avoid. But I wanted something different, something original. Moreover, badminton is played by just 2 people. For cricket you need at least 22, for which we didn’t have a budget.

But CHIDIYA is not about becoming the best badminton player!

But CHIDIYA is not about becoming the best badminton player!

Amrohi: The main characters in Indian children’s films often dream of becoming like someone else: their hero, their role-model. I never had those dreams. As a child my dreams were very simple: “this holiday I want to buy a remote controlled car”. And then I worked hard to make it happen. Like Shanu and Bua, they have no bigger goal, they just have a simple dream and will do anything to make it come true.

Any other striking elements from your childhood were processed in the script?

Amrohi: Bua asks his mum repeatedly how he was born. This is something I always asked my mother as a child, but the question was never answered correctly. She usually told me I was found in a field, or brought by an angel. And, of course, there are references to certain problematic situations in India. Still there are children who start working at an early age since there is no money to pay for their education. I wish this was not the case, but it still is.

Did any particular difficulties occur in the filmmaking process?

Did any particular difficulties occur in the filmmaking process?

Amrohi: Finding the right actors was impossible. Almost every child back there in Mumbai must have been to one of my castings. While writing a story, I’m imagining the adult actors and how they would look. But for children’s roles, there are no standard models. You only hope that one day you’ll meet the right ones. Svar Kamble and Ayush Pathak come very close to what I had in mind. Ayush is exactly like Bua, asking the same questions, making the same faces, while Svar (Shanu) seems more mature. When casting actors as ‘one family’ there should at least be a natural family feel among them and a certain physical resemblance, to make them look like a real family.

Both your main actors were debutants.

Both your main actors were debutants.

Amrohi: Most of the time I was like a father to them, and I always got them in the right mood for every scene. Preparing a happy scene, I was extra friendly, buying them ice cream so that their big eyes were shining. When preparing a sad scene, I made them feel troubled or frightened. Still for Ayush, who was only 6 years old, it was difficult to understand the emotions that were to his role.

How did you become a filmmaker?

How did you become a filmmaker?

Amrohi: It’s what I always wanted to do. As a child I entered the bathroom with a knife under my arm, acting in front of the mirror as if I was dying. But in a poor country you first need to secure your future, so like many directors from my generation, I studied engineering. When I got my degree at the age of 24 I left everything behind and went to Mumbai where, after eight years of trying, I finally made my first film. I had a hard time convincing my family and friends, until finally they understood this was really my big dream. My father was a writer, he knew about the importance of storytelling. I myself have always been writing stories as a child, just for the fun of it.

With your father’s approval?

Amrohi: With everyone sleeping in the same room, every night in bed I secretly tried to write my stories under the blanket, and I saved money to buy a torch. Until one night my mother found out. “What are you doing there?” – “Nothing, I’m just sleeping.” When finally she found my diary, she got very upset: “Why would you waste your time writing, while you should study mathematics?” But my father, in his bed at the other end of the room, simply mumbled: “That was a good story you wrote.” That moment was of a major importance to me. Later I started to copy stories from books, presenting them to my father as if they were my own. Until I found the confidence to write my own stories. Now there are masses of them. This film, and the next one that I’ll start shooting in December, are all based upon stories that I collected throughout the years.

One can wonder: why would a producer believe in a project like CHIDIYA?

One can wonder: why would a producer believe in a project like CHIDIYA?

Producer Akbar Hussaini: We thought this was a universal story that could connect with children all over the world. We were not very experienced in film funding, but we strongly believed in this project and with a small grouping we arranged the financing, without state funding. Films like these, that are not mainstream, ask for innovative campaigns. There are only few children’s films made in India, but there is a huge market. If only 1% of the nation would watch the film on satellite TV, we would already be successful.