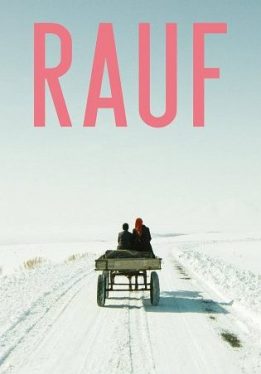

“First you’re a child and then you’re an adult”

Rauf, 9 years old, lives in a Kurdish mountain village in East-Turkey, where an unseen yet still unfinished war casts a dark shadow over the minds and moods of the people. Rauf quits school and becomes a carpenter’s apprentice. In the atelier, he witnesses the despair of the villagers, coming to order coffins for their fallen offspring.

Rauf, 9 years old, lives in a Kurdish mountain village in East-Turkey, where an unseen yet still unfinished war casts a dark shadow over the minds and moods of the people. Rauf quits school and becomes a carpenter’s apprentice. In the atelier, he witnesses the despair of the villagers, coming to order coffins for their fallen offspring.

He gets a crush on Zana, the carpenter’s daughter who has double his age. As a proof of his love, he promises to buy her a pink scarf. But the problem is that he’s never actually seen the colour before. And by the time he finds out, it might yet be too late…

In the LUCAS Festival we met both directors Soner Caner & Baris Kaya, and the young main actor Alen Gursoy.

There is a war going on in the Kars region, where the film was shot. You don’t give much of an explanation about what exactly is going on there, because it wasn’t needed?

There is a war going on in the Kars region, where the film was shot. You don’t give much of an explanation about what exactly is going on there, because it wasn’t needed?

Baris Kaya: We don’t care about the conflict, we care about the consequences for our hero. He is living with war; it’s a part of his everyday reality. Soner found a perfect solution to make that clear: he wrote a story about coffins. We didn’t want to show the war directly, no images of soldiers, guerrillas, blood or guns. We simply show a problematic situation, seen through the eyes of a child. Masking this as a story about coffins was a brilliant idea.

The war is fought ‘in the mountains’.

Baris: That’s a Turkish saying. “He is going to the mountains” has nothing to do with hiking or skiing, it means: he is joining the guerrillas.

Mainly young people are fighting?

Soner Caner: Nobody goes into the mountains at the age of 30. They’re going very young, 16 or 17 years old, and they live there all their life, until most of them die. In this region, mothers and fathers are sad about losing their children, but somehow they feel proud too. Who dies in the mountains, becomes a martyr.

How is it nowadays to make a film about a political conflict in Turkey?

How is it nowadays to make a film about a political conflict in Turkey?

Baris: The child’s perspective gives the film a different angle. So many children, whether they’re Kurdish or Turkish, are harmed by war. That’s not politics, that’s simply reality. In one scene a guy gets on the bus to join the Turkish army in Istanbul, while the other one goes to the mountains to join the guerrillas. Being Kurdish, you can have one brother in the army, and one joining the guerrillas. They even might fight each other one day. With those scenes, we’re putting an issue on the table. If then the audience goes political, this is our achievement. If the audience doesn’t go political, this is also our achievement.

Soner, you grew up in that village?

Soner: RAUF is a personal story, shot in my native village in Kars, south-east Turkey, near the Armenian border. I lived there until I went to Istanbul at the age of 13. Rauf is re-living my childhood years very realistically. His house used to be our home, the old woman is my grandmother.

Has life in the village changed a lot ever since?

Has life in the village changed a lot ever since?

Soner: Not much. Changes only come slowly to the villages.

Baris: People there are living their lives the same like 100 years ago, except the coming of television. Now they can watch Kurdish channels on satellite TV. There isn’t always water or electricity and it snows eight months per year.

Soner: Only twenty days per year we heat our homes. All the other days, even when it’s terribly cold, people just wear extra layers of clothing.

Are there particular details from your childhood that found their way into the movie?

Are there particular details from your childhood that found their way into the movie?

Soner: Selling fox skins to pay when the toy-seller came to the village. That’s what we did for real. Making scarecrows to scare people, or burying dead animals with all ceremonial. In every bus, always some older person was sitting next to the driver, talking. The song in the bus was the one always played in my youth. Every time I got on the bus, I heard that song and I hated it. It’s a Kurdish song in storytelling style, so boring for children. I felt like being tortured by that song.

Baris: All actors were Kurdish locals. In those places, children grow old at an early age. They’re considered adults. When they speak, people listen, and their voice is taken as seriously as an adult’s voice. There are no teenagers in the village. First you’re a child and then you’re an adult, maybe at the age of 11. You have to grow up very fast.

Leaving the village at the age of 13 to Istanbul must have been a shock.

Soner: It was! Being surrounded by all these buildings I felt like suffocating. I was used to the great wide open. Even now, I still feel claustrophobic in closed spaces. I have good memories to my village days, I just played and worked and nothing bothered me.

One last detail about village life: what about those dogs?

Soner: In winter wolves, foxes and jackals come to the villages and you need dogs to fight them. Those dogs are always aggressive, almost wild, like wolves. Due to that, even nowadays I’m still afraid of dogs.

Baris: The dog in the movie is huge. Still they told us it’s only a small one. When our crew came with 40 strangers, the dogs were locked away as they would attack us if we set foot on their territory.

People in the villages don’t speak much.

Soner: Most people have lost at least one or more family members. Usually they simply mind their own business. Religious feasts and weddings are the only time they get together.

Baris: There is a constant sadness, the pain about the losses is always there in the people’s eyes. They’re scared for what might come. Probably in five years Rauf will go to the mountains too. His mother already knows. The situation in those villages has been getting worse over the last two years. There was a peace process going on since 2004, but now war has started again.

One thing I found peculiar: many children’s films state that you can make your dreams come true only by going to school. RAUF isn’t exactly promoting education.

Baris: Rauf’s father and even his teacher do not really care about education. Only his mother sees education as the last chance to keep her son from going to the mountains. Without education, Rauf is a lost cause.

It’s impossible not to get struck by the beauty of the landscape and its dramatic colours.

Baris: The location was truly amazing. A lonesome and forgotten place. Wherever you put the camera, the picture looks astonishing, like a painting, with wonderful, heroic sunlight.

This landscape plays a meaningful role in the story.

Baris: It’s in every picture, while all the time the story is driven by those coffins. In my favourite scene, Rauf is measuring a mother in order to make a coffin for her son, who had the same size. Or in the closing scene, when a boat floats on the river, taking the coffin of a girl to be buried next to her mother. Or when you see the empty chair, you wonder what happened to the old woman who used to sit on it. We leave that question open. In this region, so many people are lost and nobody knows where they have gone.

How did the two directors start working together?

Baris: We were involved in one film, me as second director, Solen as art director. We became friends, and then partners in the same company. As a director, I consider myself lucky to have Solen as my best friend, because he is such a good script writer, always open for suggestions. We made the film together, as one Turkish (me) and one Kurdish (Soner) director. That was an important statement. If we can write a script and make a movie together, how can we not be able to live together? Nevertheless, from now on Solen and I each will make our own movies. Working with two directors is too hard for the crew: in the end they didn’t know whose orders to follow. It was very special, but it was a one-time-experience.

Alen, how did you end up in this film?

Alen Gursoy: My mum works in Baris’ office, and I sometimes come to visit her there. One day they were looking for actors, I auditioned and I got the role. I had to stay in the village for four months. During every break, I was rehearsing with the acting coach. I think I was destined to start acting, as my parents named me after Alain Delon.

How was it for an Istanbul boy to go to Kars?

Baris: It was hard for him to even understand the villagers. They speak a very different type of Turkish. Alen lived for a month with those two local boys, just to pick up the language. At first they were fighting all the time, they considered Alen a silly city boy. Afterwards they became good friends. Every six months they come to Istanbul to see each other. For three days they’re all staying in my house, they ruin the entire place, and then they go back.

Rumours say that RAUF might be chosen as this year’s Turkish Oscar competitor.

Baris: Maybe, or maybe not. One day they tell us they really want us, the other day they’re saying it’s impossible for a Kurdish film. We’ll see. We expected to maybe win some awards in Turkish festivals, but we could never foresee RAUF to be screened in the Berlinale, and in 50 festivals afterwards.