“I’m fighting what I see every day in the New York City streets”

Pierre Dulaine is currently based in Lebanon, as a jury member for the Middle East ‘So you think you can dance’ edition. He took a few days off to visit Brussels on the occasion of the Filem’on children’s film festival. I’m rather wary, as the Mr. Pierre we see in DANCING IN JAFFA is so charismatic and ‘bigger than life’ that I can’t be but disappointed when meeting him in real life. But I’m not! Pierre Dulaine is a chatterbox, charming and eloquent, describing himself justly as ‘a people’s person’: “I’m comfortable with people” and he has the gift to make other people feel comfortable too.

Pierre Dulaine is currently based in Lebanon, as a jury member for the Middle East ‘So you think you can dance’ edition. He took a few days off to visit Brussels on the occasion of the Filem’on children’s film festival. I’m rather wary, as the Mr. Pierre we see in DANCING IN JAFFA is so charismatic and ‘bigger than life’ that I can’t be but disappointed when meeting him in real life. But I’m not! Pierre Dulaine is a chatterbox, charming and eloquent, describing himself justly as ‘a people’s person’: “I’m comfortable with people” and he has the gift to make other people feel comfortable too.

May I have this interview from you, please?

Mr. Pierre Dulaine: With great pleasure!

Can you give us an impression on what sort of place the city of Jaffa is?

Can you give us an impression on what sort of place the city of Jaffa is?

Mr. Pierre: I can’t tell you much about Jaffa nowadays because I don’t live there. Jaffa was originally a Palestine city. That’s where I was born in 1944. But when the new people came in the early 40’s, a very high percentage of Palestinians fled from Jaffa. Only few stayed behind in their senescent homes, while in the city of Tel Aviv brand new villas were built by the Jewish community. Now both areas have merged into one big city. Many Palestinians in Jaffa don’t have the money or permits to renovate, so the old buildings are knocked down and new buildings arise. Jaffa is now very, very expensive, because it’s such a nice, sought after place.

What is your personal bond with the city?

Mr. Pierre: My grandfather bought 3 plots of land and built homes like Arab people do: for the son, the daughter, the other daughter… I was born in one of those houses. But I was only 4 years old when we left. My emotional connection solely comes from what my mother told me. My mother is catholic and Palestinian, my father is protestant and Irish. When leaving Jaffa in 1948, we went to Ireland, but were not accepted there because of my mother’s religion. My father’s family was not as kind as they could have been. After one year we went back to the Middle East, to Aman, in Jordan. That’s where I grew up. On November 2nd 1956 we had to leave Aman in a hurry because of the Suez crises. As the Brits and French were kicked out of Egypt, it was no longer safe for us to stay. My parents lost their home twice: once in Palestine and once in Jordan. We went to England, and at the age of 14 in Birmingham I started ballroom dancing. The rest is history.

Now you went back to Jaffa with a project.

Now you went back to Jaffa with a project.

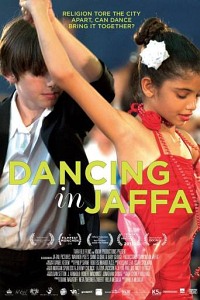

Mr. Pierre: I have this program called ‘Dancing Classrooms’, a social and emotional arts and education program, designed to cultivate essential live skills in children through the practice of social dancing. I founded the program in 1994 in New York and it has now spread over 31 cities in 5 countries. The film TAKE THE LEAD (2006) about my life, played by Antonio Banderas, has helped the project spread all over the world. After working in ‘challenging schools’ in New York City, I thought it would be great to go back to Jaffa and work with both Palestinian and Jewish Israeli children to make them dance together. Dancing once made a big difference for me: as a child I was shy, with no front teeth, I spoke English with a foreign accent, I was bullied at school… But dancing made me stand up straight. I thought this could make a big difference for the children in Jaffa.

In DANCING IN JAFFA the director stays completely out of the picture.

In DANCING IN JAFFA the director stays completely out of the picture.

Mr. Pierre: Diane Nabatoff, who produced TAKE THE LEAD, knew of my dream. She found the money and the Israeli director Hilla Medalia. Hilla and I had a very good working relationship, she is a lovely lady. But I was very much focused on my teaching job, I knew nothing about what Hilla did ‘after school hours’: following the children into their homes and playgrounds. Even when seeing each other every day, we didn’t have time to chat.

The program of ‘Dancing Classrooms’ goes twice a week, 10 weeks long, so there is already a storyline built within the project. But the writing comes afterwards, sitting through 450 hours of footage. In the editing process, that’s where the individual stories come bubbling up.

Are you happy with the result?

Are you happy with the result?

Mr. Pierre: Of course I am! I can’t believe this all really happened. It is difficult to be objective about something you are involved in, but… I’m very proud that I was part of it.

Failure was not an option, you say. We see you in some tough moments, when the project is taking a difficult start. How heavy was the pressure to make it work?

Mr. Pierre: I’ve had challenges wherever I worked with children, but never as much as this time. And I never before felt so much respect for what I did. Excuse me for saying this, but especially for the Arab children I desperately wanted this project to succeed, because they don’t have equal citizenship in Israel. I wanted to give Palestinian Israeli boys and girls a chance. When I can get an Arab boy to stand up straight, elegant, and dance with his partner, who happens to be a Jewess, he will realise: I did as good as she did. I wanted them to work together as a team, being proud about themselves. This is something that happens to them so seldom. We were bringing lives in motion.

How strong was the resistance you had to fight?

How strong was the resistance you had to fight?

Mr. Pierre: You know the reason why I was successful with the project? I speak Arabic with a local Palestinian accent. I told the Palestinian parents their children could do better at school when they felt better about themselves. I was literally welcomed into their homes and hearts, even if from a Muslim point of view, boys shouldn’t dance with girls. I think they really trusted me, and that was wonderful. The situation was different with the Jewish parents. Their children could get dancing lessons for free. Let’s do it! But then other thoughts came out, using words so ugly that I’m afraid to say them out loud ‘dancing with the enemy’, dancing with a ‘dirty Arab’. Those types of words must have resonated in some brains – of course not all of them. I started with 150 children, and ended up with 125. We lost only 25 children, for several reasons.

In general the movie makes a distinction between ‘Jewish’ and ‘Arab’ people. You are the only one using the word ‘Palestinians’.

Mr. Pierre: To be politically correct, we should say Israeli Palestinians. An Arab could as well be from Egypt, Morocco, Algeria or Lebanon… And they don’t like to be called Arabs, they only speak Arab as a common language. I never use the word Arab. They are Palestinians!

It turns out in many countries the film will be screened for a young audience. How much should they know about this situation to capture the true essence of the movie?

Mr. Pierre: In America we had a 40+ audience. But in several European countries the film will tour through schools with a study guide. That’s very useful to get my message across, a message about tolerance and confidence. But I wonder who’s going to sit with the children and teach them? From what angle will they look at history? I hope it will be the correct angle. As long as both sides are represented, everybody can make up their own mind.

Let’s talk about dancing! Why ballroom dancing?

Mr. Pierre: I’m not teaching them ballroom dancing. I’m not teaching them to become champions. With all respect, being a champion myself all over the dancing world, ballroom dancers are the worst for the job. I have developed the ‘Dulaine method’ to instruct teachers on how to work with children. It’s all about respect and compassion, about (body and verbal) language, humour and joy, being present, etc. All teachers in ‘Dancing Classrooms’ must take these elements in account.

You approach the children with a particular tone: very exuberant, overacting sometimes.

Mr. Pierre: Sometimes? You mean: all the time! I don’t have children myself, but I love them. Children read you like animals do. In 5 seconds they know whether they’ll like you or not.

Throughout the movie, for me you’ve become the ultimate personification of the true gentleman.

Mr. Pierre: The old school film stars only left their homes well-coiffed and dressed. Nowadays people care less. You could say that I’m old school. Working with children, I want to be a positive role model. I feel comfortable wearing a tie; I think I have 140. My image has always been with a tie, looking as elegant as I possibly can. I wear my jackets buttoned, I don’t own a pair of jeans and I don’t have much casual clothes. I share the old, polite manners with this new generation, fighting what I see every day in the New York City streets.

It’s not only in the clothes; it’s also in the way you behave.

Mr. Pierre: You don’t get a second chance to make a first impression. Body language is everything. When I was in Tokyo, I couldn’t wait to get back home. Those people were very kind, but I couldn’t understand the Asian body language. It was the first time in my life I didn’t feel comfortable with people.

There is one particular child that breaks everyone’s heart: Noor. What is your perspective on her story?

Mr. Pierre: Noor is half Arab, half Jewish. She’s walking two lines, without a father to guide her. At her home a mattress standing against the wall is turned into a bed at night, while Noor and her sister sleep in a bunk bed. There is no money, no space and no grandeur. Noor was a bully who hardly came to school. When she started dancing she came to school every day. Her life changed, she blossomed. For the first time ever she had a classmate visiting her at home. Suddenly she’s accepted, because of her dancing.

Have the children seen the film?

Mr. Pierre: At the premiere in Tel Aviv, Hilla, the teachers and I sat with them, hugging them constantly. We were afraid for Noor to see herself crying at her father’s grave. You know what she told Hilla afterwards? ‘I didn’t see myself often on the screen!’ Can you believe that? What a prima donna!

Does the film summarise correctly the achievements you made with this project?

Mr. Pierre: It’s all summarised in my two favourite scenes: after the competition, you see a crowded dance floor, all of them dancing meringue. Can you tell who is Arab and who is Jew? No. Then there is the very last scene: one Arab, one Jew together in a boat, rowing towards the future. A clever ending and a perfect metaphor for this film.

How will you ensure the results of the project will not vanish in thin air over the years?

Mr. Pierre: You know what I found out yesterday? We started with 5 ‘Dancing Classrooms’ schools in Israel. Several Jewish dancing teachers were sent to America for teacher training. But now we’re sending a hijab lady, 28 years old, who is going to be our new dancing teacher in Haifa. If I can get a Muslim lady to shake hands with a man and teach dancing… That’s a great start. It’s unbelievable. If you change the children, you can change the parents, and in that way you can change the world. During the dancing contest in the film, all parents sit together, cheering and chanting. One of them is a lady, completely covered. You know what she bought for her daughter? A fashionable maroon dress with spaghetti straps, because she wanted her to be amongst the others. That was fantastic.

Gert Hermans